The Excalibur

If you get to steal only one of my guitars, steal the Excalibur. The catch? I will have to kill you…

The Excalibur is my primary instrument, and considering the things I own it is easily my most beloved possession, even though I own other pieces of gear with higher street value. I modified this guitar extensively and now it rivals – and in some respects even surpasses – the best guitars I’ve ever had the pleasure to try (but not to own).

The Excalibur started its life in 2000 as a regular Epiphone Les Paul Standard manufactured in Korea. I received it for my 18th birthday from my parents! (Yes, this happened many, many years ago.) And so our relationship began…

I quickly fell in love with this instrument, however, as I got more serious with playing the guitar I became tired of some annoying defects. My primary aim with the modifications was fixing these, while also implementing enhancements which would elevate the guitar’s quality to the next level (to be at least on par with the real Gibson Les Paul).

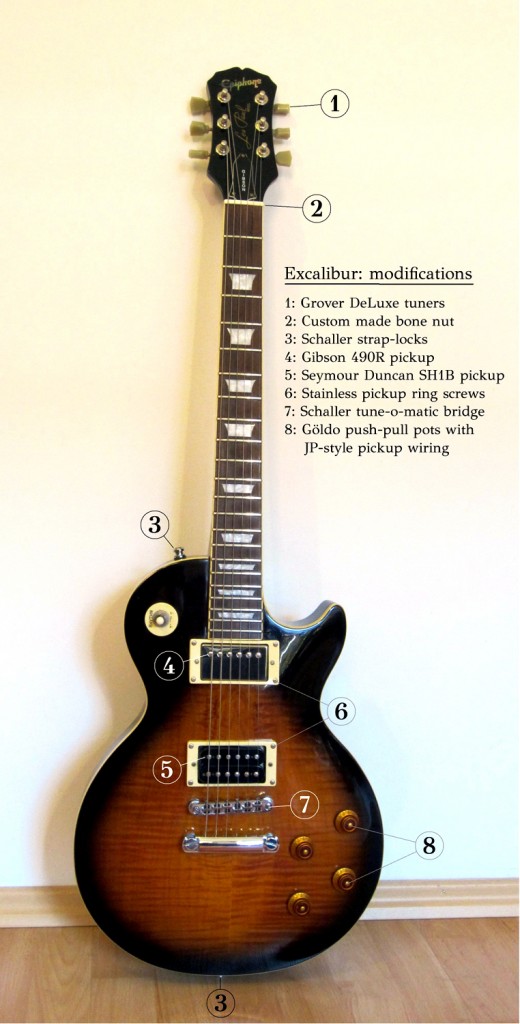

One of my main hurdles was that the instrument would always detune, especially with my style of aggressive, messy blues-phrasing with lots of bends. So the first step was to change the crappy Epiphone tuners to a set of Grover DeLuxe tuners. The selection algorithm: 1) go to local music parts shop with guitar in hand; 2) shift through all available stocks of tuner sets until a set with appropriate sizing is found, one that, once the old tuners were removed, would fit nicely in their place. Much to my horror, when I later proceeded to actually remove the Epiphone tuners from the headstock, I found that these tuners had relatively thin axes and the holes in the headstock wood were matching in diameter. However, the Grover pieces – while sporting the same exterior sizes – had considerably thicker axes and would not fit into the smaller holes. I had no other choice than to drill the mahogany with the only tool I had at hand, a low-budget household power drill.

PU switch is original, labelling too…

The detuning problem was now solved – the guitar would withstand considerable abuse with little need for repeated tuning. However, the real fun would start when I began to use my guitar on loud band rehearsals: plugged into a Marshall half-stack on mid volume, standing two meters from the stack an uncontrollable feedback sound would ensue. Even after muting the strings with both hands. Subsequent studies showed that I experienced the effects of microphonics first-hand. The Epiphone pickups proved to be defective: insufficient wax potting resulted in microphonic sensitivity causing intolerable, high-pitched feedback.

So the pickups had to be changed. After some research I decided that I would bite the bullet and in the same run, also try extending the sonic versatility of the guitar. I have read about guitar electronics before and contemplated some experiments with coil-splitting circuits. Now was the perfect moment – I only needed to sort out a few things: 1) what pickups to use (and where to buy them); 2) what kind of pots do I need (and where to buy them); 3) how to actually build them together. Since I’d always admired the stunning array of tones from Jimmy Page’s guitar (mostly heard on studio albums he did with Led Zeppelin), I naturally wanted to emulate some of that goodness. I knew Page had also had his guitar modified and also used push-pull pots to trigger some non-conventional pickup wirings (coil splitting et al), so why not go down his route?

Researching the Internet for the state of the art of the famous and widely used Jimmy Page guitar wiring, I finally settled on using the so-called Les Paul Twenty Dual master design, published under this link1. This is not the exact version JP used in his guitar, but a slightly changed (and enhanced) reincarnation of it. I decided on implementing this one based on the clarity and understability of the wiring diagrams and the high number of possible combinations (a surprisingly large number of which actually proved to be usable). Now I knew I needed four identical (500 kΩ audio taper) push-pull pots with dual circuit switches. Thankfully I was able to locate suitable parts manufactured by Göldo in a local shop.

Pickups! Always a matter of personal taste, with a multitude of options… With limited funds, I decided to play it safe in the neck position and purchase the neck pickup that is standard in Gibson Les Pauls: the Gibson 490R. Just another visit to another local shop. Last leftover piece in stock. Piece of cake.

With the bridge pickup I decided to be more adventurous. I wanted something more exotic, and sought to diverge from simply upgrading to the quality of a modern Gibson Les Paul. Again, I looked at JP’s 1959 Les Paul (his #2) and decided that I liked the concept of having a naked (coverless) bridge pickup… I only needed the sound to match that mental image. Now came another round of visiting music equipment stores… until I found, much to my pleasure, the Seymour Duncan 59 Model Humbucker (SH1B) claiming to be an exact replica of the 1959 PAF humbucker. Just what I was looking for. The catch: only available in two-wire version (and in fact, this time again it was the only piece left in stock). I decided to go for it and later extend the wiring to four-wire so I can have the coil splitting I need with the JP-style wiring. Thankfully, after reading up on the subject, I decided it was a reasonably safe operation to do.

Now came a happy period of rocking out… the sound I now got from the guitar was downright gorgeous (I had to realize how poor the original Epiphone pickups were, even with all the microphonics discounted), the feedback issues were gone and I could play for extended periods without always tuning. However, with countless hours of abuse, the frets and the tune-o-matic bridge started showing signs of wear. I had no illusions regarding the quality of the latter. I took the guitar to a local musical instrument repair shop for fret grinding and installment of a new tune-o-matic manufactured by Schaller. (Next time around, frets will also need replacement.) Much to my delight, they also endeavoured to trim the Gibson bone nut material I picked up on one of my earlier scavenger hunts, and replaced the original plastic nut, exactly replicating its dimensions. To top it all off, they also had stainless screws to replace the original screws fixing the plastic pickup rings to the guitar body. Some of those were at this point rusty beyond recognition… now everything became shiny clean.

At some point I removed the original cream-coloured pickguard; I just prefer how it looks this way. I didn’t need it anyway: I’m picking the strings, not the wood, and I tend to rest my pinky on the edge of the bridge pickup’s plastic ring… I also installed Schaller strap-locks to be able to quickly put my guitar strap on (and take it off easily). I now have these strap-locks installed on all my guitars so the same strap can be used for all. Very convenient, I can only recommend it.

It was in this state that I started recording Decline in 2011. I’ve been extremely happy with the guitar; I could always get the tone I wanted out of this instrument. In fact no other electric guitar has been recorded on the album. I also love the way it looks (the Epiphone logo on the headstock - a pearl inlay - is especially beautiful). All in all, I was lucky that the body itself (the wood material, the woodwork and the paint job) were of reasonable quality. Fret placings, while not 100% precision, are also not that bad (in higher positions, some notes are a bit off, mostly on E6 and A, but I can live with that).

For the sake of reference, here’s how the push-pull pots function:

-

The normal state, when all pots are pushed in: everything works as you would expect on an ordinary Les Paul.

-

Pulling out the bridge tone pot switches the bridge pickup from serial humbucker to parallel, or, in case the neck tone pot is also pulled, to single coil.

-

Pulling out the neck tone pot switches the neck pickup to single coil, and in case the bridge tone pot is also pulled, it also switches the bridge pickup to single coil.

-

Pulling out the bridge volume pot puts both pickups in serial mode and bypasses the selector switch. Thus both pickups will be in series, regardless of the selector switch position. In this position the bridge volume and tone control work regularly as master controls, while the neck tone control works like a treble booster, brightening up and broadening the sound in this so-called broadbucker configuration.

-

Pulling out the neck volume pot puts the neck pickup out of phase. The effect is audible when both pickups are selected, that is in serial mode or, when the guitar is in parallel mode, with the pickup selector in the middle position. Moreover, when the neck pickup is in single coil mode, this switch selects which coil will be on (pushed in: adjustable coil; pulled out: stud coil).

1 Locally hosted copy of the images here and here, in case that forum thread ever disappears.