Resurrecting an old dictionary

Moving your life permanently to another country is not for the faint of heart. It is a nontrivial enterprise on so many levels. It becomes even more challenging in case you do not yet speak, at a sufficiently high level, the language of your destination country. A good translation dictionary is a must, and as part of the definition of “good”, I mean one that directly bridges the new language to your fairly obscure native tongue.

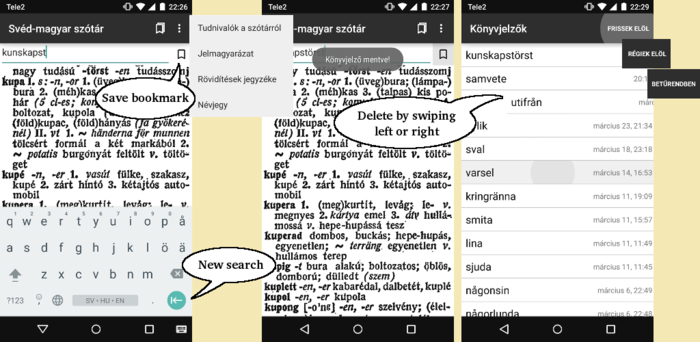

This is why I set out to create the Swedish-Hungarian dictionary for Android. Simply put, it is the Android edition of the only existing mid-sized translation dictionary from Swedish to Hungarian.

First published in 1969 with no prior art in its class to build upon, the majority of its words was collected and most of its articles written from 1958 up to its publication. As you might correctly guess, judging by today’s standards this volume is ridiculously outdated. It has no mention of several modern words of today’s everyday conversational Swedish, such as mysig, schyst or even kolla. Nor does it offer the informal, everyday, “real” meaning of others, such as fika. Fifty years is a long time, especially when you consider the sweeping cultural changes of the last half century, and the linguistic ones that inevitably came with those.

The dictionary has been reprinted several times. I have a copy of the sixth edition from 1992 on my bookshelf, and there are even later prints from the 2000s, even though retail availability of the book was sporadic at times. In my view, the original edition was, at the time of its publication, a state of the art dictionary – well-selected, rich and deep content, resulting from a scientific approach and a decade of hard work by a group of Hungarian linguists. Hats off to all of them!

Sadly, the publisher never got around to revise the book’s content. Actually, looking closely at a few copies, I am quite convinced that throughout the decades, the same hot metal pressing stereotypes were used for the bulk of the book. It is instructive to look at printing errors characteristic of this ancient press technology, such as the inverted y in yttre on printed page 952, but also at plain old typos such as the extra m in varjämte, spelled as varmjämte (but appearing at the correct lexical ordering position between varjehanda and varken), on pp. 897. All of these artefacts are there regardless of the year and the edition.

As outdated as it might be, this dictionary was (and is) still very important to me as a native Hungarian looking to get deeper into the Swedish language. Simply because it is the only existing one of its kind. A treasure trove of exemplary sentences, idioms, and of course more words than you would ever need to recognize. I have been looking hard and no other dictionary comes even close.

The start of an obsession

At the time I got into learning Swedish, initially as a hobby towards the end of 2013, I was on the hunt for usable learning material. I was looking to study on my own, in a country where extremely few people speak or apparently care about the Swedish language. I stumbled upon this gem of a dictionary, not even in physical form, but only as digitized by Project Runeberg. I quickly assembled a script to recreate a PDF from the scanned pages, complete with bookmarks for reasonably speedy navigation, and used the resulting book for countless hours of self-study. You can create this book, too, by following these instructions, if you are so inclined.

The PDF was a usable solution to the “dictionary problem”, and I did use it quite heavily in the next eighteen months leading up to my relocation to Stockholm. Towards the end I even managed to buy a physical copy of the sixth edition which I planned to carry with me and use it “if all else fails.” (I did.)

Enter smartphone

After moving to Stockholm, I realized that my new, Swedish phone had a 5.5” screen with full HD resolution, non-stop 4G connectivity, and computational capacity several orders of magnitude above the aggregate of what was used to land on the Moon. Also, as I was in Sweden now, my brain was constantly stimulated both visually (via ads and signs) and verbally with the “real” (non-textbook) Swedish language.

I thought about this as I was commuting on the Stockholm subway. I had never written an app for Android before – maybe this was the perfect time? Indeed, it seemed like a good deal to get a taste of Android development and create a mobile dictionary I would have really, really loved to carry in my pocket in the preceding two years.

If only a day had 52 hours, or more. Life and the Universe had successfully kept me from pursuing this idea for another year. Finally, during the fall of 2016 I got around to reading some introductory Android tutorials and started playing with some example projects. From there it was smooth sailing, although with chronic pains.

The torture never stops

I am used to working with interactive, incrementally compiled

languages where I can use a REPL (read-eval-print loop) and quickly

experiment by changing parts of the program as it is running without

always having to re-start everything. Android development was an

anti-experience in this regard: only compiling and installing the app

to my phone via ./gradlew installDebug took about 50 seconds… a

really, painfully slow wait each time!

This extremely long feedback cycle was the icing on the cake of actually having to write Java and XML code. Or rather, copy-pasting different solutions together – due to the sheer size of the community, it was very rare that I did not immediately find something along the lines of what I wanted. Still, dealing with these languages in their rawest form was mind-numbing. I went for the bare-bones experience: I did not use the customized Android IDE so I would be forced to see and understand everything in the source. But it felt more like chopping the woods rather than an intellectual exercise.

Ingenuity was needed, though. The raw OCR I extracted from the pages published by Project Runeberg had a tremendous amount of errors, which is quite understandable when you look at the (sometimes very poor) quality of the scanned images. So I decided to reduce the room for error in the search algorithm, by doing an index-based lookup to get the first possible page of a word, and then doing a sequential search. This way, the problem got smaller but search was still not usable. Due to the two-column page layout, the search needed to go through both columns for one index entry. Sometimes even more, for multi-page articles. This increased the probability of a false match above the limit that I deemed acceptable. I decided to try some kind of pre-processing where the keywords would be marked in advance, and the search would only take these marked keywords into account. I had a hard time coming up with a sufficiently good algorithm; I spent weeks tuning some mildly advanced heuristics and at the same time fixing typical OCR errors in bulk via Emacs dired’s query-replace-regexp.

Another problem was getting the images into acceptable form. The scanned pages were unevenly warped and rotated. Thankfully, I found an excellent tool called ScanTailor that I used with very good results. I only had to go through a mere thousand pages, manually define the rotation and de-warping parameters, and select the areas of the two columns of text via drawing bounding boxes with the mouse. This work took about three months of all my free time; I finished it around New Year 2017. It was a huge relief to be done with that. I think I lost part of my brain, though.

The application started to get into usable form, so I began to test it on some other devices. Mainly emulators, but also my old Galaxy S2. As soon as I tried to launch it, it immediately crashed. I figured out that the OCR pre-processing was taking so long that the Android system decided to kill the app. (On my “normal” phone, this only took about a second.) Fortunately, it was straightforward to move this OCR pre-processing step into the build toolchain and include a binary containing the pre-processed text array in the application. This got me past the initial crash, but I got more crashes while searching and scrolling. It was necessary to reduce the memory footprint – fortunately enough, I had a few pieces of low-hanging fruit in terms of code re-organization that resulted in the level of optimization needed. There was one instance where I could move a garbage-generating String method out of the innermost loop of the search method to the toplevel (only running once per search). The app began to run reliably on all the devices and emulators I tried, and I was happy.

I started playing with the idea of publishing my app on the Google

Play app store. I had a feeling that probably nobody is going to

clone my repo, follow the (long and adventurous) build instructions

and install the .apk on their phone (that they had to enable

Developer Mode on), just for the sake of trying this app. I quickly

realized two obstacles. Firstly, I had to pay $25 to Google for the

privilege of setting up a developer account to publish my free app to

the world. Secondly, I learned that the app size limit is 100 MB. My

.apk at this point was close to 150 MB. I knew that was going to

cost much more than $25 to get under 100 MB.

Thankfully, I found the pngcrush program and with it, a possible way

to reduce the size of the image resources that made up the bulk of the

application’s size. Indeed, pngcrush did a very good job, although

at the expense of a lot of CPU time. But it was not enough. I also had

to reduce the resolution of the images from the 600 dpi of the

original scans to somewhere above 300 dpi.

After about six months of absorbing literally all of my free time, my dictionary application was ready for publication. I released it at the end of March, 2017.

Conclusion

It’s been a long and rough journey. At times, the only thing that kept me going was that I really wanted to have the end result in my hands. I also put myself under some time pressure since I already had the next thing I was going to work on, and it came with a deadline.

I learned quite a few things on the way.

-

The development cycle is painfully slow. Really, really painfully slow. I feel this alone is enough to keep me from doing more Android development in my free time.

-

It is probably worth using the Android IDE instead of the bare-bones approach that I took.

-

Gradle? I like my hand-written Makefiles, thank you. They work, I know how they work, and they are very fast. I also prefer to type

makeinstead of hairy stuff like./gradlew installDebug(that you tend to forget all the time). I didn’t even try to learn how to extend the Gradle build system with the preparatory tasks needed to get and pre-process the imagery for this app. An additional DSL (domain specific language) for defining my tasks (or whatever they are called) was not something that interested me at that point. So I just added a bunch of shell scripts to be run in order, by whoever was bootstrapping the repo for building the app. Documented in the obligatory README. (I figured I don’t need to be a Gradle expert, as long as I’m literate.) -

Keeping a reasonable subset of the Android SDK with emulators, API versions, etc. downloaded on my machine took up several tens of gigabytes of space. I don’t know about you, but to me this feels like a lot of space to waste, especially on a laptop with an SSD. (Note that I only used the SDK, as I did not use any Android IDE, only the command line tools and Emacs.)

-

To me, Android development still feels like embedded development. The RAM and processing power the app must fit into is severely constrained. Especially if you want to make an app that runs on most of the actual devices currently in circulation, not just your own device (that is arguably higher-end than average).

-

Coming up with the actual code necessary to achieve a certain feature or effect is usually not hard. Growing it into a nicely testable, coherent architecture for the whole app is harder.

-

Navigating the official Android developer documentation (both the Javadoc for classes and the Android developer tutorials) is a breeze. Knowing what you actually need or want to use in terms of the API is a different story.

-

Unit testing your Android class is a pain. No, really. Whoever thought that declaring half of the most important Android API classes to be

staticwas a good idea? (I am looking at you,Context… certainly every class I wrote had at least a function that takesContextas input.) Please take note: Static classes and unit testing do not play well together! -

Google demands a $25 fee to become an app publisher on Google Play Store, even if your app is completely free and contains no ads. In other words, Google made me pay for the privilege of publishing my free app, even while fully knowing that I will not make any monetary returns on the investment of my most valuable asset – my time. I paid because I wanted the app to be easily obtainable by all those who might need it; people without the know-how of installing an app from a third party source. However, this way Google actively encourages the proliferation of low quality adware instead of high quality apps (free or not). It also encourages people like me (who might scratch their own itch by writing an app) to just publish an

.apkon their website (or even just a source repo) and get on with their life.

So… I guess writing your own Android app is a cool thing, even more so if it is highly useful to yourself and potentially several other people you care about. But for my part, I am back to functional programming large-scale backend systems… for fun and profit.